Chapter 3 – My Summer Montana Childhood

My mother, who raised four boys while her husband worked long hours, found some relief from her everyday parenting duties during the summers. One summer, in the mid-60s, an opportunity arose when a friend of hers was traveling to Wisconsin by train from Baltimore. She placed my brother, Bruce, and me – ages 7 and 10 respectively, on that same train in Baltimore, sending us across the country to Montana for a month-long visit with our grandparents. My brother and I were excited to go on a train for this long journey which required several days. However, I do not recall my mother’s friend being around much during the train ride to Chicago. She may have been in an adjacent car or somewhere nearby. After arriving at the Chicago train station (one of the largest in the world) with the train stopping every two hours all night long, I remember asking the conductor “where the Great Northern to Seattle was.” He pointed me down to the end of the platform, so my brother and I proceeded ahead.

(Dr. Bruce Anderson and Dr. Stephen Anderson)

My mother’s friend eventually departed at the Wisconsin La Crosse Station, and we continued to Montana on our own. I consider us to have been “free-range” kids in those days. We wandered about the train to the dining car and enjoyed going up to ride in the “dome cars” where there were beautiful views of the Minnesota wilderness and North Dakota and Montana prairies. The train stopped frequently on its journey westward at every small town. Usually, these stops were brief, and as we neared Montana my brother and I had to be more alert. The term “whistle stop” had a real meaning. The train would stop in the smaller towns, blow the whistle and you had less than 10 minutes to get off the train with your baggage, otherwise, the train would continue to move on. As we were two children ages 7 and 10 with no cellphone communication, the idea of being stuck on a train all the way to Seattle where we knew no one had left me on high alert.

Our stop was in Havre, Montana in the northeast part of the state. Hopefully my grandparents would be waiting for our arrival. I was riding in the dome car as we passed through Bismark, North Dakota and realized that perhaps the next stop might be Havre. I went back down to find my brother asleep. I woke him just in time as we pulled into the Havre train station, and we grabbed our bags. As I got off the train, I looked up and was relieved to see my grandparents, the only two people waiting at the station, as very few people got off in Havre. I have no recollection of any conductor or anyone else watching over us during the latter part of this trip. The current generation of parents would probably find the prospect of putting two children on a two-day train trip across the country somewhat horrifying, as life today is very different.

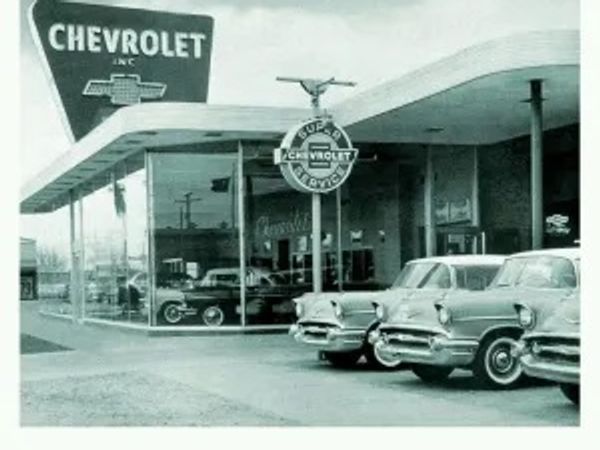

My grandfather grew up in Albert Lea, Minnesota, the son of Norwegian immigrants and farmers. He lost his eye to a buggy whip when he was 18 years old, preventing him from being able to serve in World War I. His brother enlisted and was eventually killed in the trenches of France, so perhaps I am grateful for this injury or my grandfather may have met with a similar fate. Despite this injury, he decided in the early 1920s to move west to Montana and served a brief stent as a cowboy. He attempted homesteading in eastern Montana, but unlike his cousins, his homestead failed as there was too little water in eastern Montana. With the invention of the automobile and its widespread arrival to the general public, he was offered the only Chevrolet dealership at the time in Harlem (Blaine County), Montana. The rest of his career was spent working at this local car dealership and repair shop in this small town of Harlem.

In rural Montana – the Montana that I grew up visiting – there was no speed limit for automobiles. My grandfather, despite his previous injury, frequently drove over 100 miles an hour in his pick-up truck. My grandmother, however, was terrified of driving. She got her license late in life and never went over 40 miles per hour, as all the roads in northeast Montana were only two lanes. The sheer terror of riding with both of them as a child still remains with me. When my grandfather picked us up from the train station that day, and drove us from Havre to Harlem, his speed often exceeded 100 miles per hour. However, when riding on the same road the very next day with my grandmother at the wheel, our speed never topped 40 or 45 miles per hour. Other vehicles sometimes came up behind us going anywhere from 100 to 120 mph which made this almost equally as risky a drive. During my grandfather’s lengthy driving career, he managed to run over at least 20 animals, including approximately 10 deer, multiple porcupines and a large cow. Fortunately, no humans were ever hit.

My grandfather would frequently take my brother and me fishing at the various locations surrounding Harlem, Montana. This was the highlight of our summer. However, we would often ride in the back of the flat-bed pickup truck that he was driving at his usual high rates of speed, and we would have to hold on for dear life as we flew down those roads.

As an auto dealer, one of his most frequent clienteles were the Native Americans from the adjacent Fort Belknap Indian Reservation. Often, after receiving their government paychecks, and being able to make a down payment on a truck, they would come in to purchase a vehicle. However, sometimes they would renege on their payments and my grandfather would be forced into the difficult action of having to repossess those vehicles on the Indian Reservation. I have one recollection of accompanying him with another man on one of these occasions. We pulled up to a shoddy looking trailer that night and repossessed the truck while armed, although repossessing vehicles at night was not my idea of a fun summer vacation.

As I mentioned, the highlight of my summer visits to Montana were the evening fishing and fly-fishing trips at the local reservoirs. We would also fish the adjacent Milk River. My grandfather would set lines overnight with several Native American assistants. One of the assistants was a man named Charlie. During his later years, I remember seeing him occasionally walk the town in full Indian chieftain headdress, oftentimes inebriated. I am not sure whether he was once a famous Indian chief or not. One night, he was found passed out on the train tracks and subsequently run over by one of the Great Northern Railroad trains.

Fly fishing was always a big part of my childhood summers spent in Montana. I caught my first fish on a fly at the age 4. My dad set me up on a beaver dam in the wilderness of the Swan River in northwest Montana with a fly rod and a small royal coachman fly while he proceeded upstream to fish some bigger holes. I casually flipped the small fly into the pool behind the beaver dam and instantly, a small 6-inch rainbow trout grabbed the fly. I was “hooked’ for life. In the summers to come, I fly-fished every evening with trips to the various reservoirs of the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation with my grandfather and his local cronies.

In the mid-70s, our trips to Montana became a cross-country family drive. One year, as we pulled into a gas station in northeast Montana after a long drive, the station attendant looked at my hair, which was down to my shoulders as was the case with most teenage kids in the 70s, and said “We don’t serve no hippies here” and denied us gas service. In those days, all gas stations were full service. My parents were shocked and I presume they eventually found gas at another station along the way. Later that same trip we proceeded to visit my cousins, who owned a large ranch in northeast Montana. As I arrived at the ranch, I began hanging out with one of my oldest distant cousins who was busy cleaning his gun. He was wearing a flannel shirt and blue jeans. He seemed to be sizing me up – my long hair and John McEnroe-style blue tennis shorts. He was particularly interested in the bumper sticker on the family station wagon that stated, “Pride in the Tribe.” He looked at me with a kind of disgusted look as he was cleaning his gun and said, “You ain’t no Injun-lover are you?” pointing to my bumper sticker. I tried to explain to him that I attended the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia and our mascot was an Indian and that the bumper sticker only reflected the college logo “Pride in the Tribe.” But I felt his opinion of me was permanently formed and there was little that could be altered from that point on. I was an eastern hippy wearing short-shorts that supported Native Americans. Luckily this opinion that had developed may have saved me from the hard farm labor that they did every day. The original plan of having me help bale hay and work on the farm seemed to have disintegrated. I was left to study organic chemistry during the day for my pre-med classes and go fly-fishing at night.

One summer, my grandfather had a rubber raft that we borrowed, inflated and took out to the Snake Butte Reservoir in the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation. I was fishing from the rubber raft with one brother and my father. Some Indian kids found this sight amusing as my one brother was very pale. They wasted no time in firing BB shots at us to sink our raft. Luckily, they were not bullets and although we did not sink it was very disconcerting. I came to the conclusion that my one brother, who had a fair complexion, made us somewhat of a target for the local Indian kids looking for some fun. Luckily, the raft was not damaged. My father loved to paint pictures of this reservoir. There is actually a painting he did of the reservoir and the scenic view behind it hanging in our family home.

I eventually returned to eastern Montana with my wife, high-school aged girls, and my parents. There was an Indian pow wow scheduled on the Rocky Boy Reservation south of Havre. My girls were excited to go and see the Native Americans in their dress. I decided it would be worthwhile to attend, but only on a Sunday afternoon rather than an evening, when there would be no worry of any alcohol-related disturbances occurring. When we were leaving for the pow wow, I was surprised that my father had declined to attend. Despite being an academic, liberal Johns Hopkins Professor, powwows were not something that was ever a part of his childhood roots. My mother, however, gladly attended and thoroughly enjoyed our time with the Native Americans in their native dress and dance. Our adult children to this day remember it fondly and the friendliness of the people. Although, when I did pull up in the parking lot, we found multiple shell casings from gunshots the night before and large piles of empty Colt-45 malt liquor bottles confirming my decision that it was best to attend on a Sunday.

Copyright © 2023 Anderson Radiology - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.