Chapter 4 – Fishing Ritual Ends in Whitewater Disaster

As children, my brothers and I looked forward to the end of winter and arrival of March, because this was the beginning of both the trout and shad fishing seasons in the State of Maryland. When the opening day of trout season arrived, my father would pull us out of school, and we would arrive at the trout stream called “BeeTree Run” at approximately 5:00 AM to secure our position for the opening cast at 5:30 AM. Beetree Run was crowded shoulder-to-shoulder with other fishermen who had the same goal.

Our secret weapon, we discovered early on, was that cheese was the actual perfect bait for these hatchery-raised trout. However, not just any cheese would do – only Velveeta cheese would do the trick! Swiss cheese, American cheese, even various French cheeses all failed to produce a hit. So, during the trip to northern Baltimore County in the wee hours of the morning, we would stop at our favorite local bait shop – 7-Eleven – and purchase two large packages of Velveeta cheese to guarantee our success. After catching our limit of trout, my father would take us back to school where we arrived at approximately 10 am.

My father (who was a Hopkins medical doctor) would always write us a note on Johns Hopkins medical stationary that stated his sons “had a case of fishing fever” and would be late for school that day. Somehow, the school office would see the Hopkin’s stationary with the diagnosis of fishing fever and allow us to return to school with no questions asked. Obviously, with the current climate of school absenteeism being what it is, this would most likely not go over very well today.

My favorite fishing experience happened with the arrival of the shad in the Susquehanna River in northern Maryland. This would also require an early start, as it was a very long trip meaning that we would miss the entire day of school. The day before this trip, my brother and I traditionally walked to the Sunny’s Surplus store to purchase various colored “shad darts.” Oddly enough, every year it seemed to change as to which color the shad would be biting.

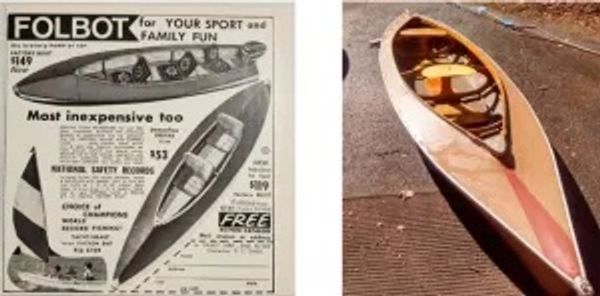

One cold early day in March, with the temperatures being in the mid-40s, my father decided that our friends, the Converys, who lived in Philadelphia, should meet us at the halfway point on the Susquehanna River to go fishing.. The Converys made the logical decision to rent a motor boat. I was excited, however, that my father decided to purchase a two-man “early extended” version of the kayak called a Folbot. We loaded the boat on top of our 1966 Chevelle station wagon, and we drove up to the Susquehanna River.

When we arrived, the Conowingo Dam was on full speed with their sirens blaring warning of high waters. This turned the adjacent lower Susquehanna River into a torrent of whitewater. When the dam was off, or minimally running, it is a very slow peaceful lake-like river, but when the dam is on, it turns into a 20-30 feet deep fastmoving torrent. As we arrived on the banks of the river, my dad surveyed the waters. He decided since we had no anchor, that we should paddle out to a small nearby island. He would secure our boat to a tree with a long rope, so we could fish safely. As it was 45 degrees, I was wearing my ski jacket, hat and long pants. I got into the front seat of the Folbot, while my six-year-old brother and my dad were in the back seat. I do not recall ever putting on a life jacket. We paddled out into the middle of the river to the island. My father tied a rope to the tree on the island and tied the rest of the rope to the back of our Folbot kayak. We drifted approximately 40 feet from the island, safely tethered, and began to fish. The problem was that as the current continued to increase, the boat began to sway back and forth. With the fast-moving current the boat suddenly capsized. Luckily my six-year-old brother was wearing a life jacket, and my father was able to grab him immediately while holding on to the Folbot. Unfortunately, I was swept downstream in a raging current of whitewater – a nine-year-old wearing a heavy ski jacket and long pants. The Converys, who were fishing nearby in their rental motorboat, saw what happened. Mr. Convery quickly attempted to start his engine, but to no avail. I remember seeing him repeatably pulling the starting cord on the motor but it would not start. I was treading water and drifting for what seemed to be an eternity. No one was in sight. I began to get cold and hypothermic. Several hundred yards later and yelling for help, I had reached my greatest moment of despair, when suddenly some huge arms grabbed me from behind and pulled me into a boat. I had not seen other fishermen that day besides ourselves, but apparently, there had been other shad fisherman on the far side of the river who had seen us capsize and rushed over to my aid. I never saw these people again, and I do not know who they were, but they were my guardian angels on that day. Mr. Convery eventually got his motor started and headed over to rescue my dad and my brother.

We sat on the banks of the Susquehanna River, all three of us having lost our glasses, and wondered how we were going to get home. I knew that this was probably the end of that Folbot kayak. I was right, because when we arrived home, my mother promptly told my father to sell the kayak. This boating accident, from then on, was referred to as “the incident.”

Fifty years later, I was having lunch with the Converys and learned that to this day they still were deeply disturbed by their inability to come to my rescue that day. I am forever grateful to that shad fisherman who rescued me. I never knew his name or saw him again after that fateful day.

After “the incident,” it was several years before I had the courage to go in boats again. In fact, during college I was on the William and Mary Canoe Team. Given my past history of capsizing, maybe this was not the greatest decision, but I loved whitewater canoeing. Our team had qualified for the eastern regionals in Morgantown, North Carolina on the Catawba River below Lake James. It was being hosted by Appalachian State University. I had noticed when I arrived on the river with my teammate for the doubles competition, that a large crowd had gathered on the bridge over the Catawba River where the worst section of whitewater was. It was like a crowd at an auto race gathering to see a wreck. I also noticed a completely flattened canoe smashed against one of the pilons under the bridge. I thought to myself, “Boy that looks like a tough section of river.” My teammate and I started down the Catawba River effortlessly making all the gates. Eventually, we hit the bridge where the crowd had gathered. We zipped under it and made a rapid turn upstream to get through the gate. As we pushed hard to get through, we immediately capsized. The crowd cheered of course, as it seem that this was what they were waiting for. Once again, I found myself drifting down in whitewater, however, this time I was an adept swimmer and I was not nine years old. As I was in my 20s, it was a nonissue to swim to the side of the river and then hike upstream. Our canoe had to drift downstream in order to be pulled out. Having been through this before, I felt it was no big deal, but now unfortunately, I was disqualified from the Eastern Regionals. Luckily I was able to complete the solo competition without incident, but nowhere near the top of the field.

In medical school there was also an incident where I was sailing with a classmate, Dr. Roy Bands and our sailboat capsized in Middle River, Maryland. At that point in my life, being a veteran of capsizing, I was unaffected by this. Roy was also an adept sailor and swimmer and was able to right the boat without incident.

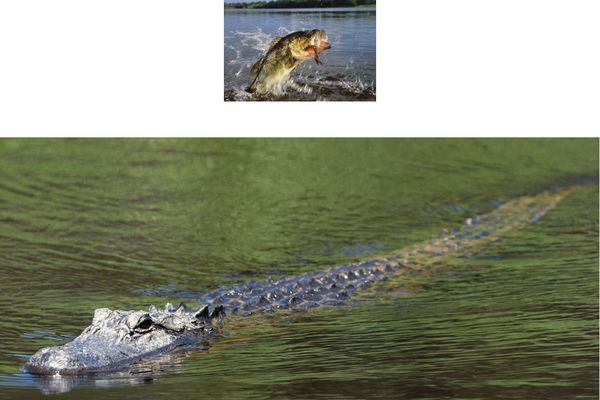

One day during my radiology residency, I was bass fishing from a canoe in the far corner in an uninhabited lake adjacent to my apartment complex. I made the unfortunate decision of standing up in the canoe while fishing. As the sun set, I noticed several alligators nearby and decided maybe it was time to go home. Right at that moment, the largest bass I had ever hooked decided to take my line. It came flying out of the water and looked to be at least 10 pounds in weight. The size of the of the fish alone, was quickly overshadowed by the sheer terror of capsizing with multiple alligators in the lake. After the pandemonium subsided, I found myself swimming among the lily pads still holding on to my fishing pole. It was difficult to fight a bass this size while treading water with large alligators lurking nearby. As the line snapped, my dream bass took off to a distant part of the lake. I then observed my canoe filling up with water with the front pointing in the air, sinking titanic-style. It was probably a three-quarter mile swim to shore. Thanks to my canoe training in college, I knew how to un-swamp the canoe and was able to turn it over and bail enough water to paddle my way home. Interestingly, more alligators congregated in the vicinity of my canoe, but none ever approached me. This incident couldn’t help but bring to mind an x-ray I had seen of the arm of a canoeist bitten off by an alligator after his boat had capsized while bass fishing. This x-ray was shown to me during my interview for a radiology resident at the University of Florida.

These series of adventures eventually lead me to transition to wade fishing or fishing from stable boats. My days of stand-up fishing from a canoe were over.

In closing, I reiterate that to this day, I am forever grateful to the unknown fisherman of the Susquehanna River who pulled a 9-year-old boy out of the cold 40-degree water.

Copyright © 2023 Anderson Radiology - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.